Ángulo entre dos rectas

De Wikillerato

(→Ángulo entre dos rectas) |

|||

| (10 ediciones intermedias no se muestran.) | |||

| Línea 1: | Línea 1: | ||

| - | |||

==Ángulo entre dos rectas== | ==Ángulo entre dos rectas== | ||

| Línea 20: | Línea 19: | ||

s | s | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | en un mismo plano paralelo a | + | en un mismo plano paralelo a ambas rectas. |

| - | Las | + | Las rectas se proyectan en un mismo plano porque, en general, |

| - | + | no tienen porque encontrarse en un mismo plano ( no tienen porque ser | |

| - | + | coplanarias ). | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | no tienen porque encontrarse en un mismo plano. | + | |

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| Línea 36: | Línea 29: | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\alpha | \alpha | ||

| - | </math> | + | </math>, |

| - | y otro mayor, que seria el suplementario de | + | y otro mayor ( o igual ), que seria el suplementario de |

<math> | <math> | ||

\alpha | \alpha | ||

| - | </math>, | + | </math>, |

<math> | <math> | ||

180 - \alpha | 180 - \alpha | ||

| Línea 68: | Línea 61: | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

\mathbf{v} | \mathbf{v} | ||

| - | </math> | + | </math>, |

se puede calcular con la siguiente fórmula: | se puede calcular con la siguiente fórmula: | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \cos \left( \, \widehat{r,s} \, | + | \cos \left( \, \widehat{r,s} \, \right) = \frac{\left| \, \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{v} \, \right|}{\left| \, \mathbf{u} \, \right| \cdot \left| \, \mathbf{v} \, \right|}} |

| - | + | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | Calculando el | + | Calculando el arcocoseno del resultado obtenido aplicando la fórmula anterior se |

obtiene el ángulo que forman las retas | obtiene el ángulo que forman las retas | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Línea 93: | Línea 85: | ||

Calculemos el ángulo entre las rectas de ecuaciones | Calculemos el ángulo entre las rectas de ecuaciones | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Línea 112: | Línea 107: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

La recta | La recta | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

r | r | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | viene dada como la intersección de dos planos ( el plano de ecuación | + | viene dada como la intersección de dos planos ( el plano |

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \pi_1 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | de ecuación | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | 0 = x - 2y + 3z | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | y el plano | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | + | \pi_2 | |

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | + | de ecuación | |

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | + | 0 = 2x - y + 4 | |

</math> | </math> | ||

). | ). | ||

| Línea 128: | Línea 134: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| - | Un vector director de la recta | + | Un vector director |

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \mathbf{u} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | de la recta | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

s | s | ||

| Línea 137: | Línea 147: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

en su ecuación, es decir: | en su ecuación, es decir: | ||

| + | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Línea 143: | Línea 154: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | + | Podemos obtener un vector director | |

| - | + | <math> | |

| - | + | \mathbf{v} | |

| - | Podemos obtener un vector director de la recta | + | </math> |

| + | de la recta | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

r | r | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | multiplicando vectorialmente un vector perpendicular al plano | + | multiplicando vectorialmente un vector perpendicular al plano |

| - | + | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \ | + | \pi_1 |

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | + | por un vector perpendicular al plano | |

| - | por un vector perpendicular | + | |

| - | + | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \ | + | \pi_2 |

| + | </math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Un vector | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \mathbf{n}_1 | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | </ | + | perpendicular al plano |

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \pi_1 | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | lo podemos obtener de los coeficientes de x, y, z en la ecuación del plano | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \pi_1 | ||

| + | </math>: | ||

| - | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | + | \mathbf{n}_1 = \left( \, 1, \, -2, \, 3 \, \right) | |

</math> | </math> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | De la misma forma obtenemos un vector | |

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \mathbf{n} | + | \mathbf{n}_2 |

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | </ | + | perpendicular al plano |

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \pi_2 | ||

| + | </math>: | ||

| - | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \mathbf{n | + | \mathbf{n}_2 = \left( \, 2, \, -1, \, 0 \, \right) |

</math> | </math> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| Línea 185: | Línea 207: | ||

El producto vectorial de ambos vectores, | El producto vectorial de ambos vectores, | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \mathbf{n} | + | \mathbf{n}_1 |

</math> | </math> | ||

y | y | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \mathbf{n} | + | \mathbf{n}_2 |

</math> | </math> | ||

es | es | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| + | \mathbf{v} = | ||

\left| | \left| | ||

\begin{array}{ccc} | \begin{array}{ccc} | ||

| Línea 202: | Línea 225: | ||

2 & -1 & 0 | 2 & -1 & 0 | ||

\end{array} | \end{array} | ||

| - | \right| = \left( \, 3, \, | + | \right| = \left( \, 3, \, 6, \, 3 \, \right) |

</math> | </math> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | El ángulo que forman las rectas | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | + | r | |

</math> | </math> | ||

| - | y | + | y |

<math> | <math> | ||

| - | \mathbf{ | + | s |

| - | </math> | + | </math> |

| + | es, por tanto | ||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | <math> | ||

| + | \mathrm{arc} \cos \frac{\left| \, \mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{v} \, \right|}{\left| \, \mathbf{u} \, \right| | ||

| + | \cdot \left| \, \mathbf{v} \, \right|} = \mathrm{arc} \cos \frac{\left| \, \left( \, | ||

| + | 1, \, -1, \, 2 \, \right) \cdot \left( \, 3, \, 6, \, 3 \, \right) \, | ||

| + | \right|}{\sqrt{1^2 + \left( \, -1 \, \right)^2 + 2^2} \cdot \sqrt{3^2 + 6^2 + | ||

| + | 3^2}} = \mathrm{arc} \cos \frac{1}{6} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | |||

[[Category:Matemáticas]] | [[Category:Matemáticas]] | ||

Revisión actual

Ángulo entre dos rectas

El ángulo entre dos rectas

y

y

del espacio es el menor angulo entre las rectas que se obtienen al proyectar

del espacio es el menor angulo entre las rectas que se obtienen al proyectar

y

y

en un mismo plano paralelo a ambas rectas.

Las rectas se proyectan en un mismo plano porque, en general,

no tienen porque encontrarse en un mismo plano ( no tienen porque ser

coplanarias ).

en un mismo plano paralelo a ambas rectas.

Las rectas se proyectan en un mismo plano porque, en general,

no tienen porque encontrarse en un mismo plano ( no tienen porque ser

coplanarias ).

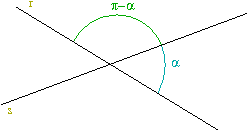

Dos rectas en el plano forman dos angulos, uno menor, llamemoslos, por ejemplo,

,

y otro mayor ( o igual ), que seria el suplementario de

,

y otro mayor ( o igual ), que seria el suplementario de

,

,

.

.

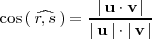

El ángulo entre dos rectas

y

y

cuyos vectores directores son, respectivamente,

cuyos vectores directores son, respectivamente,

y

y

,

se puede calcular con la siguiente fórmula:

,

se puede calcular con la siguiente fórmula:

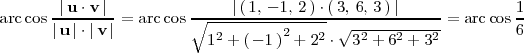

Calculando el arcocoseno del resultado obtenido aplicando la fórmula anterior se

obtiene el ángulo que forman las retas

y

y

.

.

Ejemplo

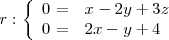

Calculemos el ángulo entre las rectas de ecuaciones

y

La recta

viene dada como la intersección de dos planos ( el plano

viene dada como la intersección de dos planos ( el plano

de ecuación

de ecuación

y el plano

y el plano

de ecuación

de ecuación

).

).

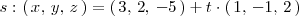

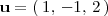

Un vector director

de la recta

de la recta

es el vector que multiplica al parametro

es el vector que multiplica al parametro

en su ecuación, es decir:

en su ecuación, es decir:

Podemos obtener un vector director

de la recta

de la recta

multiplicando vectorialmente un vector perpendicular al plano

multiplicando vectorialmente un vector perpendicular al plano

por un vector perpendicular al plano

por un vector perpendicular al plano

.

.

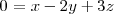

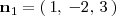

Un vector

perpendicular al plano

perpendicular al plano

lo podemos obtener de los coeficientes de x, y, z en la ecuación del plano

lo podemos obtener de los coeficientes de x, y, z en la ecuación del plano

:

:

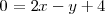

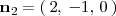

De la misma forma obtenemos un vector

perpendicular al plano

perpendicular al plano

:

:

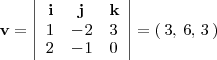

El producto vectorial de ambos vectores,

y

y

es

es

El ángulo que forman las rectas

y

y

es, por tanto

es, por tanto